This is one of the most significant copyright cases of the year. One primary reason for the said distinction is the position this decision takes on the fair use doctrine being an important element of copyright. On May 18, the Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS) held that the Andy Warhol Foundation’s use of Lynn Goldsmith’s photograph in commercialising an image “Orange Prince” does not favour AWF’s fair use defence against copyright infringement.

Case Background

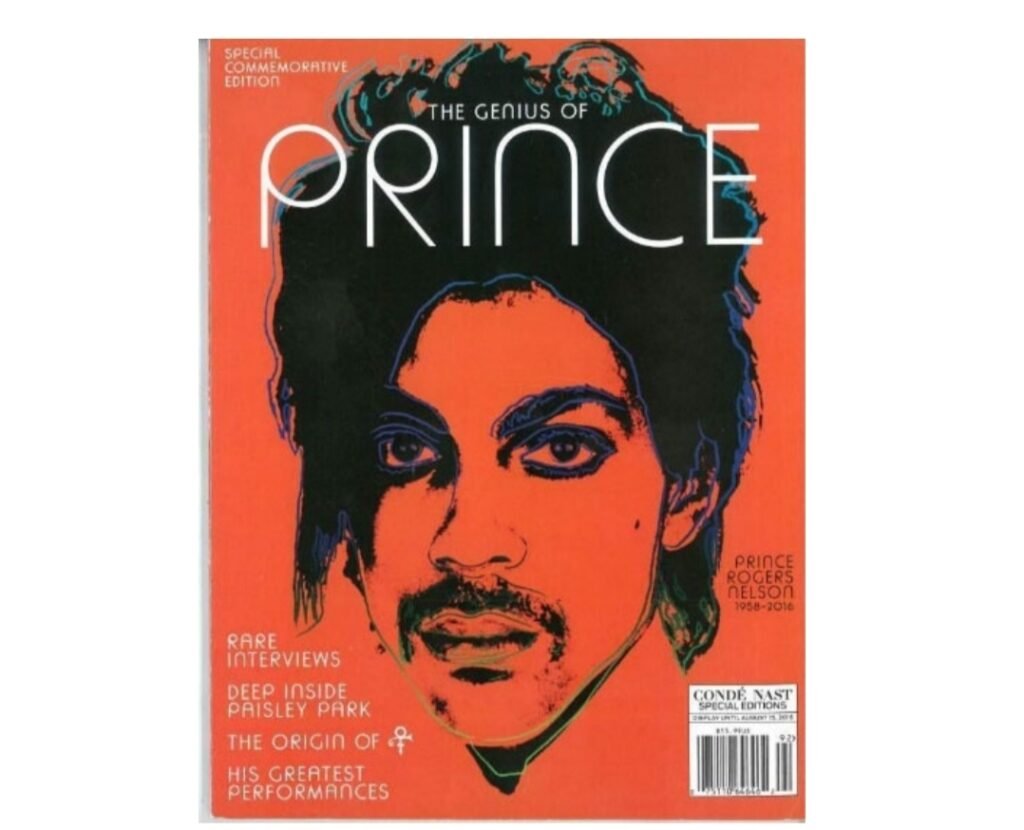

In 2016, the petitioner Andy Warhol Foundation for The Visual Arts (AWF) licensed to publisher Condé Nast for $10,000 an image “Orange Prince”, an orange silkscreen portrait of the late musician Prince created by pop artist Andy Warhol- to appear on the cover of a magazine cover celebrating Prince after his death that year.

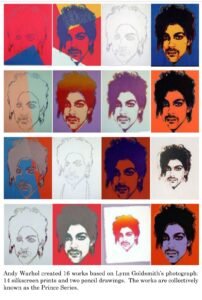

“Orange Prince” is one the 16 works now known as the “Prince Series” that Warhol derived from a copyrighted photo of Prince taken in 1981, by photographer Lynn Goldsmith, the respondent in this case. Goldsmith was commissioned by Newsweek magazine in 1981 to photograph an “up and coming” musician named Prince Rogers Nelson, after which Newsweek published one of Goldsmith’s photos along with an article about Prince. Years later Goldsmith granted a limited license to Vanity Fair for use of one of her Prince photos as an “artist reference for illustration”. The terms of the license included that the use would be for “one time” only. Vanity Fair hired Warhol to create the illustration and Warhol used Goldsmith’s photo to create a purple silkscreen portrait of Prince, which appeared with an article about Prince in Vanity Fair’s November 1984 issue. The magazine then credited Goldsmith for the “source photograph” and paid her $400.

After Prince’s death in 2016, Vanity Fair’s parent company Condé Nast asked AWF about reusing the 1984 Vanity Fair image for a special edition magazine that would commemorate Prince. When Condé Nast learnt about the other Prince Series images, it opted instead to purchase a license from AWF to publish Orange Prince. However, Goldsmith did not know about the Prince Series until 2016, when she saw Orange Prince on the cover of Condé Nast magazine. Goldsmith then notified AWF about her belief that it had infringed her copyright. AWF then sued Goldsmith for a declaratory judgment of non-infringement or, in the alternative, fair use. On the other hand, Goldsmith made a counter-claim for infringement.

The District Court considered the four fair use factors in 17 U.S.C 107 and granted AWF summary judgment on its defence of fair use. The Court of Appeals reversed this decision, finding that all four fair use factors favoured Goldsmith.

Analysis

Under the United States Copyright Act, courts are required to consider the following four factors while deciding whether the use of a copyrighted work constitutes fair use-

a. The purpose and character of the use.

b. The nature of the copyrighted work.

c. The amount and substantiality of the portion used, and

d. The effect of the use upon the potential market for or value of the work.

AWF contended that the Prince Series works are “transformative” and the fair use factor thus weigh in their favour, because the works convey a different meaning or message than the photograph. However the Court noted that “the first fair use factor instead focuses on whether an allegedly infringing use has a further purpose of different character, which is a matter of degree, and a degree of difference must be weighed against other considerations, like commercialism…”

Court said-

“Here the specific use of Goldsmith’s photograph alleged to infringement her copyright is AWF’s licensing of Orange Prince to Condé Nast. As portraits of Prince used to depict Prince in magazine stories about Prince, the original photograph and the AWF’s copying use of it share substantially the same purpose. Moreover, AWF’s use is of a commercial nature. Even though Orange Prince adds new expression to Goldsmith’s photograph, in the context of the challenged use, the first fair use factor still favors Goldsmith.”

Justice Elena Kagan, who was joined by Chief Justice John Roberts in dissenting against the majority judgment, did not mince her words. In a highly combative tone, Justice Kagan observed “the majority’s lack of appreciation for the way his (Warhol’s) works differ in both aesthetic and message from the original template. She further noted, “What is worse, that refresher course would apparently be insufficient. For it is not just that the majority does not realise how much Warhol added; it is that the majority does not care.”

Court’s Opinion

Justice Sonia Sotomayor delivered the seven-two majority judgment and observed,

“This copyright case involves not one, but two artists. The first, Andy Warhol, is well known. His images of products like Campbell’s, Soup Cans and of Celebrities like Marilyn Monroe appear in museums around the world. Warhol’s contribution to the contemporary world is undeniable.

The second, Lynn Goldsmith, is less well-known. But she too was a trailblazer. Goldsmith began her career in rock and roll photography when there were few women in the genre. Her award-winning concert and portrait images, however, shot to the top. Goldsmith’s work appeared in Life, Time, Rolling Stone, and People magazine, not to mention the National Portrait Gallery and the Museum of Modern Art. She captured some of the greatest rockstars of the 20th century: Bob Dylan, Mick Jagger, Patti Smith, Bruce Springsteen and, as relevant here, Prince.”

Justice Sotomayor noted that the first fair use factor favours Goldsmith, not AWF. She further observed,

“In addition to the single illustration authorised by the Vanity Fair licence, Warhol created 15 other works based on Lynn Goldsmith photograph: 13 silkscreen prints and two pencil drawings. The works are collectively referred to as the Prince Series. Goldsmith did not know about the Prince Series until 2016, when she saw an image of an Orange Silkscreen portrait of Prince (Orange Prince) on the cover of a magazine published by Condé Nast.

By that time, Warhol had died, and the Prince Series had passed to AWF. AWF no longer possesses the works, but it asserts copyright in them. It has licensed images of the works for commercial and editorial uses…

The magazine titled, ‘The Genius of Prince’ is a tribute to Prince Rogers Nelson. It is devoted to Prince. Condé Nast paid AWF 10,000 for the license. Goldsmith neither received a fee nor a source credit.

Remember that Goldsmith, too, had licensed her Prince images to magazines such as Newsweek, to accompany a story about a musician, and Vanity Fair, to serve as an artistic reference.”

Justice Sotomayor also highlighted the fact various magazines like Reader’s Digest, People’s, Time and Rolling Stone released special editions in honour of Prince after his death and “all of them used copyrighted photos and all of them (except Condé Nast) credited the photographer.”

Finally, countering the dissenting judges in the strongest terms, the majority opined-

“The dissent would rather not debate these finer points. It offers no theory of the relationship between transformative uses of original works and derivative works that transform originals….

And no limiting principle for its apparent position that any use that is creative prevails under the first fair use factor. Instead the defence makes a simple (and obvious) point that restrictions on copying can restrict follow-on works.”

As for the dissenting judges and their comments on the said judgement “stifling creativity of every sort”, Justice Sotomayor said-

“These claims will not age well. It will not impoverish our world to require AWF to pay Goldsmith a fraction of the proceeds from its reuse of the copyrighted work. Recall payments like these are an incentive for artists to create original works in the first place. Nor will the Court’s decision which is consistent with the long standing principles of fair use, snuff-out the light of western civilization returning us to the Dark Ages..

The dissent thus misses the forest for a tree. It’s single-minded focus on the value of copying ignores the value of original works.”

Read the judgment HERE

Author: Nitish Kashyap