The surge in artificial intelligence (AI) tools for creation has thrust into light concerns involving copyright assertion, attribution and ownership. A lawsuit filed in the U.S. District Court for the District of Colorado by Jason Allen helps illuminate one strand of some of the legal nuances and hurdles that artists face when using AI in their art making processes. The Artist, Allen, filed for declaratory relief after the U.S. Copyright Office rejected copyright protection for his AI-assisted artwork, Théâtre D’opéra Spatial. The case focuses on significant nuances concerning human authorship’s limitations in an age where artificial intelligence is becoming increasingly important in cultural output.

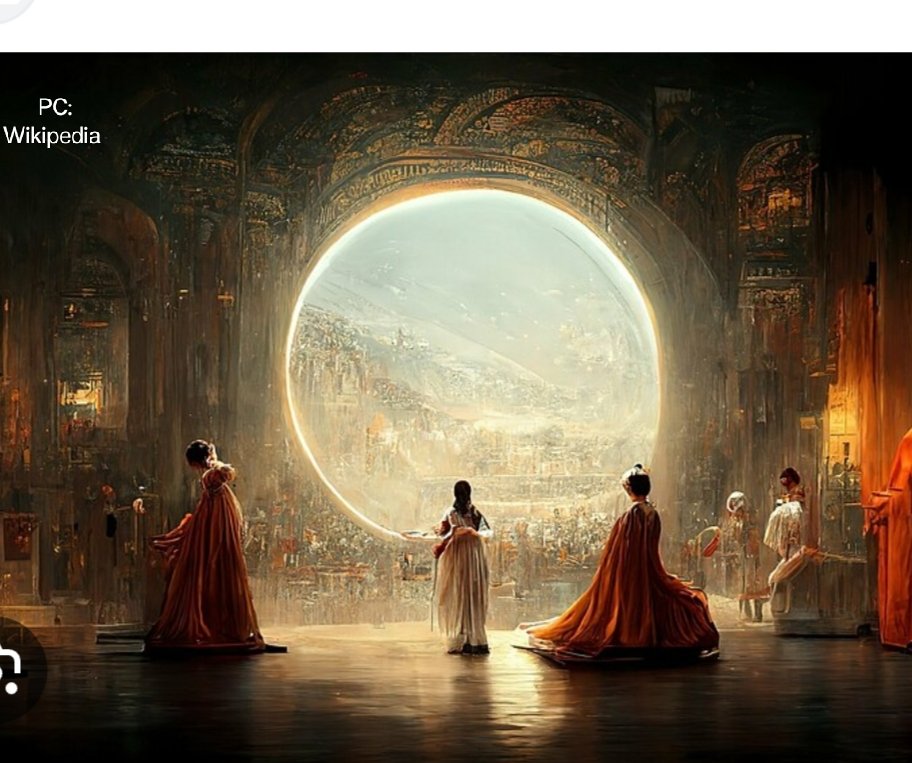

On September 2022, Allen applied to the U.S. Copyright Office to register Théâtre D’opéra Spatial, a piece he created using the AI tool, Midjourney. This program generates images based on textual prompts. Allen used it to create a detailed image of women in Victorian attire wearing space helmets, performing in a futuristic opera house. Despite Allen’s active role in the creative process, the U.S. Copyright Office denied his application, stating that the work lacked the necessary human authorship for copyright protection.

Allen then filed a case on September 26, 2024 claiming that his work was “suffused with significant human authorship” and should be copyrightable. He claimed that, though he used Midjourney to assist in this work, it was not passive; there was a great amount of human effort put in to complete the artwork. Allen started with the idea of a woman in Victorian clothes set next to futuristic features, like space helmets, and input loads of text prompts for the AI to draw it. Allen claimed that it was simply like a photographer making multiple runs in an effort to catch the perfect shot. So, over 624 iterations later he tweaked his prompts and changed the direction a little bit until an AI image came close to what was in his head. Over 114 hours later, when the final product appeared almost complete he suggested that the AI was a tool he directed, rather than the independent creator.

The U.S. Copyright Office denied Jason Allen’s application for Théâtre D’opéra Spatial on the grounds that it did not meet the standard of human authorship required for copyright protection. This decision raises broader questions about a new culture of art making and appropriate standards of copyright for the new media technologies. As a result section 313.2, the U.S. Copyright Office states that original work is needed to be protected by copyrights as it requires human creativity and skills which AI systems do not process. Section 313.2 outlines a two-part test for determining authorship: the machine must not “conceive of” or execute the traditional elements of authorship independently. Since neither condition was met in Allen’s work, the U.S. Copyright Office denied his copyright claim. Allen disputes this, arguing that AI is merely a tool, comparable to a camera or paintbrush, following human input and commands. He claims the U.S. Copyright Office’s decision unfairly penalizes artists who incorporate new technologies into their creative process. He also strongly objects to the decision given in light of, sections 310.2, 310.5, and 310.6 of the Compendium of U.S. Copyright Office Practices, which state that copyrightability should be determined by how a work is perceived, without consideration of the tools or methods used to create it. Allen’s position is that similar to other mechanical and digital technologies, AI should be seen as an extension of human creativity, not an independent author.

The denial of copyright protection created practical challenges for Allen. Since the Copyright Office’s decision, he has observed unauthorized uses of his work, including reproductions on social media and illicit sales on platforms such as Etsy. The primary disadvantage is that Allen lacks copyright; consequently, there is barely anything he can do to prevent these infringements from occurring, limiting his potential to monetize the work. This raises an important question: if Allen cannot copyright the work, who can? This legal ambiguity has created a gap, under which AI-generated works are placed at the mercy of those who produce them and exert authority over them.

Allen’s lawsuit claims that the U.S. Copyright Office’s decision violates both the Administrative Procedure Act (APA) and the Copyright Act. Allen contests that the decision not to grant his artwork copyright protection was capricious and failed to take into account how much effort he had put in creatively; He went on to advocate a copyright-agnostic approach for the work’s technical methods, and in doing so mused that AI-driven art is no different from previous technological advancements within art history such as photography or computer enabled music. These forms of arts which were earlier opposed are today acknowledged as being lawful. Allen also points out inconsistencies in the U.S. Copyright Office’s treatment of AI-assisted works. For example, the U.S. Copyright Office has granted copyright protection to artists who use AI-generated images as references for hand-painted works, yet denied protection for Allen’s work because it was not physically recreated. Allen argues that this gap undermines the critical role that human creativity plays in shaping AI systems.

This case could set a precedent as to how copyright is handled with AI-generated works in the future. The ruling might encourage more artists to embrace AI without fear of losing ownership of their work. If the court upholds the U.S. Copyright Office’s decision, artists using AI may face significant challenges in protecting their creations, which could discourage innovation in the field of art. As AI continues to influence creative sectors, the law needs to shift and help copyright laws stay up to date. Rather, the question still remains whether pieces produced with the help of AI can be referred to as true works of art made with the help of human genius. The verdict given in this case will determine whether other AI products would be afforded the protection of the copyright law in the future or not and to what extent would it influence future artistic and legal environment.

Authors: Saurojit Barua & Malvika Pandey