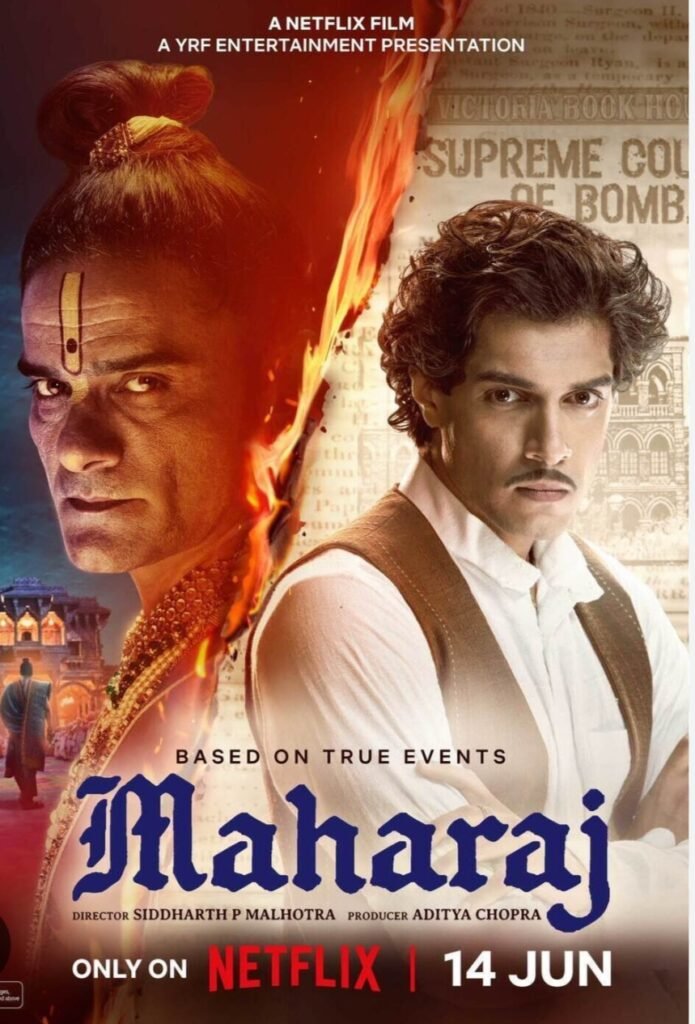

The Gujarat High Court, on June 21, 2024, vacated its ad-interim injunction against the release of the film “Maharaj”, originally imposed on June 12, 2024. The film is based on the real-life Maharaj libel case from 1862 and adapted from the 2013 book “Maharaja” by Saurabh Shah. The film features Junaid Khan, son of veteran actor Amir Khan.

The film’s premise centres around a defamation case filed by Jadunathji Brijratanji Maharaj against a newspaper article accusing him of sexually exploiting female followers under the guise of religion. The case, which became a landmark judgment, involved British judges and several controversial remarks about Hindu religion, beliefs, and practices. The Petitioners, Bharat Pranjivandas Mandalya & Ors, who identify as the members of the Vaishnavite sect Pushtimargi, claimed that the film could harm communal harmony and sentiments due to its “scandalous and defamatory language” and “is likely to incite feelings of hatred and violence against the Pustimargi sect”.

Arguments Advanced

On June 12, 2024, Senior Counsel Mihir Joshi argued that the film could incite ‘hatred towards the community’ towards their sect, violating the Information Technology (Intermediary Guidelines and Digital Media Ethics Code) Rules 2021 and the Self-regulation Code of Over the Top Technology (OTT). Accordingly, Justice Sangeeta Vishen granted an ad-interim injunction and issued notices to the Respondents, including Union of India, Netflix India, Yash Raj Films, and the Central Board of Certification.

Senior Advocate Shalin Mehta, representing Respondent No. 4, Yash Raj Films, contended on June 18, 2024, that the Petitioners’ assumption that “since the language of the 1862 judgement is defamatory, hence, the movie based on the same is also defamatory” is wrong and unfounded. The film did not contain any lines from the judgment and had received a CBFC certification. Senior Advocate Mehta cited S. Rangarajan v. Jagjivan Ram & Ors. to emphasize artistic freedom of expression and speech and Babuji Rawji Shah vs S. Hussain Zaidi (Gangubai Kathiawadi Case), the film’s CBFC certificate indicated it was not defamatory or obscene in nature. The Respondent, citing Sushil Ansal vs Endemol India Pvt Ltd argued that films based on public domain information, do not amount to defamation. They also noted that the Petitioner’s claims of secretive intentions due to no trailer no trailer was released lacked basis, as there is no rule, regulation, guideline mandating publisher to engage in promotional activities. The High Court was also informed of the Petitioner’s delayed action on the eve of the film’s Netflix release, contending it should not be entertained.

Senior Arguing Counsel Mukul Rohatgi and Jal Unwalla representing Respondent No. 5 i.e., Netflix India argued that the petition incorrectly assumed the film was based solely on the 1862 trial judgment, ignoring it’s basis on the 2013 book “Maharaja.” The Petitioners, aware of the book’s existence, deliberately failed to disclose before the High Court, leading to the grant of ad-interim injunction. Netflix relied on Prakash Jha vs. Union of India and Viacom18 Media Pvt Ltd vs Union of India,asserting that issuance of CBFC certification negated the need for further court interference. Counsel relied on Vishesh Verma vs. State of Bihar and F.A. Picture International vs. CBFC, which emphasized the importance of artistic expression and the director’s vision, stressing that preventing a film’s release stifles creativity and restricts fundamental rights. Referencing to Anuradha Bhasin vs Union of India, they also highlighted the importance of applicability of artistic expression and freedom of speech to the medium of internet and the Courts discretion in applying the test of proportionality. The Phoolan Devi vs State of M.P., was cited to support the argument that the book on which the film is based did not lead to any negative consequences, inferring that the community is likely to accept discussions on such topics.

Petitioners argued that reliance on the CBFC certificate, issued in 2023, to claim that the film complied with the Cinematograph Act, 1952 lacked merit, as there was no guarantee the same movie was being released without edits in June 2024. They reserved the right to challenge the CBFC certification. To demonstrate the film’s legitimacy, the producer offered a viewing to the court, which could lead to a reasonable decision by the Gujarat High Court. The matter was therefore rescheduled to 20th June 2024, allowing the court to view the film.

During the hearing on June 20, 2024, the Gujarat High Court considered the Petitioners’ request to block the film under Section 69A of the Information Technology Act, 2000, stating the content violated the Code of Ethics provided under the Intermediary Guidelines 2021. Mihir Joshi argued that the failure of Ministry and Authority to block the content on 11th June 2024, justified the court intervention. Citing Truth (N.Z.) Ltd. vs Holloway, the Petitioner provided that “Every publication of a libel is a new libel, and each publisher is answerable for his act to the same extent as if the calumny originated with him” and K. A. Abbas vs The Union Of India & Anr, states that, “Article 19(1) cannot be invoked to defeat the fundamental rights guaranteed by Article 21. While one may claim the right to free speech, others equally possess the right to listen or to decline to listen, ensuring that one’s exercise of free speech does not violate the rights of others”. Further cases, including Subramanian Swamy v. Union of India, Jacob v. Superintendent of Police, Ram Jethmalani vs Subramanian Swamy, etc., were referenced to underline the balance between free speech and public order, as “Article 19(1) cannot be invoked to defeat the fundamental rights guaranteed by Article 21. While one may claim the right to free speech, others equally possess the right to listen or to decline to listen, ensuring that one’s exercise of free speech does not violate the rights of others” and “mere delay or laches should not bar access to justice when fundamental rights are at stake”.

The Gujarat High Court, having viewed the film and been briefed on its story, heard the respondents’ closing arguments on 21st June 2024. Respondent No. 4 argued that the film, based on the book “Maharaja,” should not be conflated with the 1862 judgment. They cited Indibly Creative (P) Ltd. vs. State of West Bengal and Bobby Art International vs. Om Pal Singh, highlighting that films right to depict social evils or controversial topics realistically. They also contended that Rule 16 of the Intermediary Guidelines 2021 was inapplicable and that claims of incendiary content were unsubstantiated without trailers or teasers. Additionally, they submitted that if the ad-interim stay continues, the petitioner should compensate the respondents with Rs. 100 Crore for potential losses due to their substantial investment in the film.

The Petitioner, in its rejoinder, argued that even if the movie focuses on the libel case from the book “Maharaja” based on the 1862 judgment, it could offend public sentiment and lead to a law-and-order issue. They maintained that the film’s secretive release, without trailers or promotional events, indicated a deliberate attempt to conceal its storyline, which could provoke public disorder.

The Court’s Finding

The Gujarat High Court, in its order on June 21, vacated the ad-interim injunction. It noted that the book “Maharaja” had been published in 2013 without causing communal disharmony, and since the film had not yet been released, pre-emptive restrictions on freedom of expression were unjustified.

The Gujarat High Court’s decision to vacate the ad-interim injunction on “Maharaj” is a landmark affirmation of artistic freedom and the role of film in social commentary. It underscores the judiciary’s commitment to balancing community sentiments with fundamental rights. The judgment reinforces that CBFC-certified films should generally be presumed permissible for their exhibition, supporting filmmakers in their creative endeavours and enriching cultural discourse by allowing diverse stories to be told and heard.

Author: Sujoy Mukherji